From Backstage to Bye Bye Tiberias: The Middle Eastern films to look out for this autumn

The presence of Golden Lion winner Poor Things at recent film festivals has been a blessing and a curse. For film purists, Yorgos Lanthimos’ best work to date was a masterpiece, garnering unanimous love. Nothing screened in Venice or Toronto measured up to its aesthetic invention and political audacity.

For Middle Eastern films, it was an uphill battle at the festival circuit, with most falling flat on their faces while struggling to edge out competition in a cluttered autumn marketplace.

Some showed flashes of promise and admirably trod new ground, even if they did not succeed entirely. Others inadvertently demonstrated the wide intellectual and artistic gap between the likes of Lanthimos and the rest.

A case in point is Behind the Mountains, the latest release by acclaimed Tunisian filmmaker Mohamed Ben Attia, whose most recent two films, Hedi and Weldi, debuted in Berlin and Cannes respectively.

Ben Attia regular Majd Mastoura plays Rafik, a seemingly ordinary chap who suddenly and inexplicably loses his bearings by sabotaging his workplace and receiving a four-year prison sentence.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Rafik kidnaps his estranged son from his ex-wife and flees to the mountains. Having been discovered by the police, he storms into a house in a small village and holds the inhabitants hostage - all the while, trying to convince everyone that he can fly!

Ben Attia’s third feature is his weakest to date: a hodgepodge of half-baked ideas and divergent cinematic sentiments, which sorely lacks coherence.

At once, Behind the Mountains is a father-son story, a hostage thriller and a supernatural dramedy - different genres lumped together without harmony. It’s a film that wants to be multiple things but ends up being none.

We never know who Rafik really is and why he acts the way he does; nor are there allusions to Tunisia’s current reality. Without these elements, the film boils down to a trifle of a metaphor for the search for freedom.

But freedom from what? Domestic constraints? Social oppression? The burden of responsibility? We never know, and without these details it’s difficult to care about a character who represents little more than a philosophically infantile scribble.

More ambitious was Backstage by Afef Ben Mahmoud and Khalil Benkirane. The basic plot centres on the members of a pan-Arab dance group confronted by deep-seated fears and questionable life choices when their tour bus breaks down in the Atlas Mountains in Morocco.

Both plot and characterisation take a backseat to what is a delicate meditation on gender roles, Arab identity and the value of creative labour in a region where art is a luxury.

The end product is a feast for the senses. Its subtle politics, however, is its strongest asset, exploring female sexuality and self-autonomy; gender fluidity and polyamory; and the schism between the free nature of art and the restrictive, overbearing reality of Arab societies.

Not everything in the film works. The dance scenes are an acquired taste and the characterisation needs more depth, while the questionable role of art in the region - arguably the most intriguing theme of the picture - is barely touched upon.

Backstage is nonetheless a highly sensitive, aesthetically adventurous film that will reward the patience of a perceptive audience.

The Sun Will Rise and the ethics of consent

Iran has been a constant fixture in festivals the world over this year, and Venice was no different. The offerings this year shed light on both the potential and problems inherent in the gaze of filmmakers in exile.

The Sun Will Rise, is one such example, a docu-fiction by artist and filmmaker Ayat Najafi, who lives in Berlin. Set in October 2022, shortly after the Mahsa Amini protests began, the film centres on a theatre company attempting to produce a contemporary version of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata, the ancient Greek comedy about a group of women who deny their men sex in order to stop the Peloponnesian War.

Najafi’s camera captures the erupting rifts among group members who question the tone and scope of the play in the wake of the protests. The production gradually veers towards a more serious tone, as harrowing testimonies of abuse and assault the women have endured at the hands of the police begin to infiltrate the contorted narrative.

Shot largely from the point of view of the actors’ lower limbs, with their faces concealed throughout, Najafi's film fragments the Iranian female body in a way not seen before. The effect is certainly unsettling, partly for the conceptual boldness of his approach, but there’s also a whiff of exploitation and prickly sensationalism blotting the proceedings.

As the movie progresses, the barrage of testimonies grows increasingly redundant, numbing the initial shock. The visual concept of the film should be lauded for its invention, while the subject at hand remains as urgent as it was 12 months ago. But the execution is too heavy-handed, self-important and attention seeking, so much so that it’s difficult not to question the method's intention.

Additionally, there is no indication that the consent of the actors has been obtained, requiring another layer of ethical scrutiny of a film that is not as innocuous as it may appear to be.

Turkish offerings

Turkey made a comeback in Venice with two productions that illustrated both the strengths and lingering inadequacies of its independent cinema.

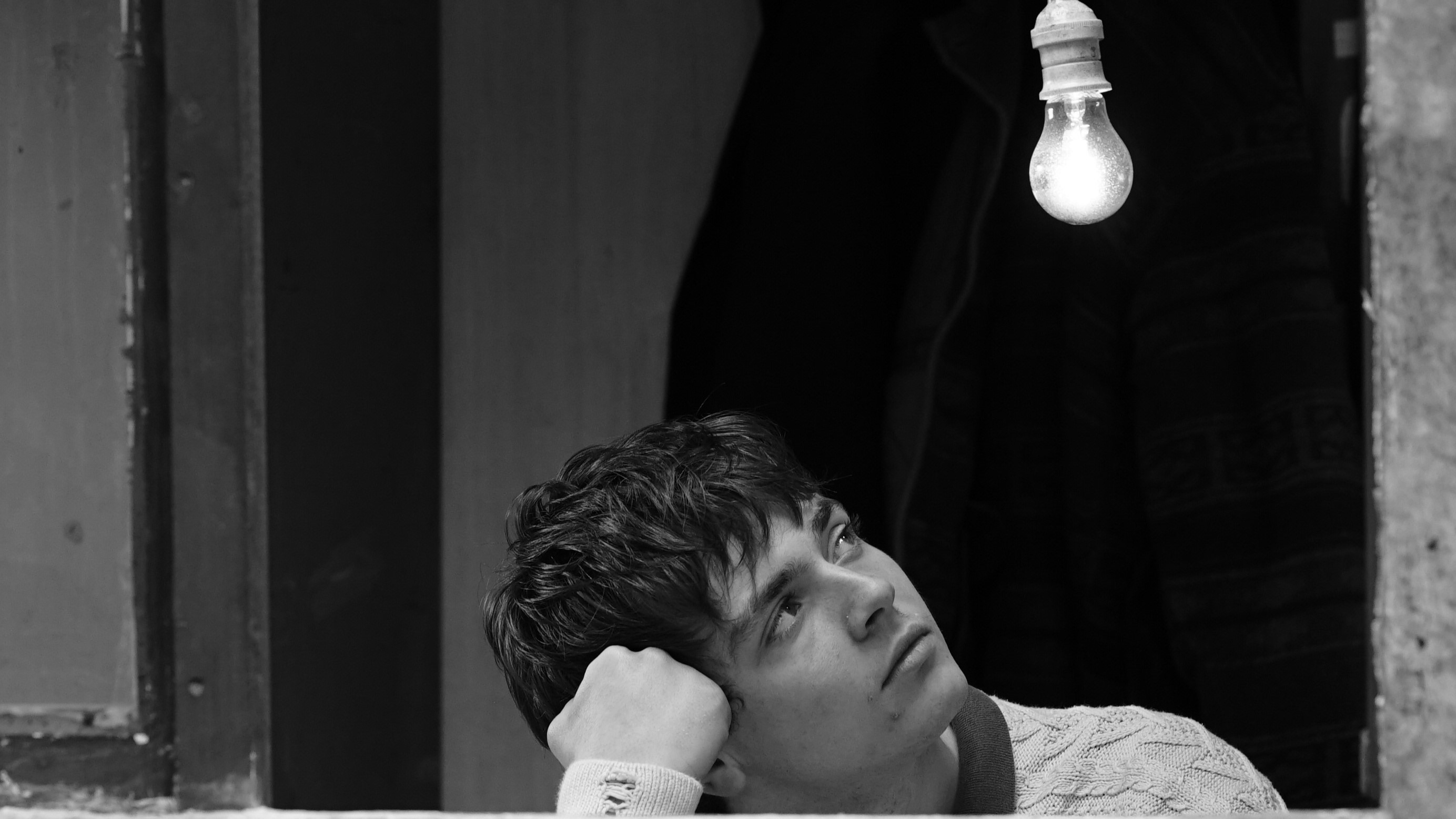

The first is Yurt (Dormitory), Nehir Tuna’s transfixing chronicle of 14-year-old schoolboy Ahmet (Doga Karakas), who is torn between his upper-class westernised school and the titular all-boys' Islamic dormitory in which his father forcibly enlists him for his religious education.

Shot in black and white, the film is set in 1997, the peak of the conflict between the traditional secular ‘White’ Turks and the burgeoning Islamic movement.

Yurt is a snapshot of a country in transition: a country divided between the traditional secularism of the founding father of modern Turkey, Ataturk, and the rising power of religion, embodied by Erdogan, whose AK Party would win power a few years later.

Tuna shrewdly adds class to the mix, a key element in this divide. The sudden conversion of Ahmet’s father to religion is depicted as a manoeuvre for political and economic gains rather than a sudden spiritual awakening.

The cruelty and repression Ahmet experiences at the dormitory mirror the oppression Erdogan would unleash later during his reign.

The film’s lack of resolution perfectly embodies Turkey’s state of mind in the 21st century: a divided nation that remains unsure which direction it needs to take; a nation that cannot identify its true identity.

Less successful is Hesitation Wound, Selman Nacar's second feature about an upper-middle-class district attorney handling the case of a man on trial for murdering the owner of the factory he works in, while she is tending to her dying mother.

Canan (Tulin Ozen), who has recently returned to Turkey after a lengthy spell abroad, is a fish out of water, striving to adapt to a place from which she has become disconnected.

Nacar confronts Canan with an assortment of moral choices, from pulling the plug on her brain-dead mother to bending the rules in order to save her suicidal client.

Undeniably engaging, Hesitation Wound nonetheless treads familiar grounds, be it in its rudimentary treatment of class or in its depiction of the moral greyness that defines urban Turkish life.

The courtroom drama lacks tension, and many of Canan’s actions are too naive to be believable.

There’s little in here that hasn't been seen or tackled before, and while the narrative does flow well, the film ultimately feels undercooked and underwhelming.

Bye Bye Tiberias

The gem of autumn's Middle Eastern selection is Bye Bye Tiberias, the second documentary feature by Palestinian-Algerian filmmaker Lina Soualem.

Soualem’s first film, Their Algeria, revolved around her grandparents and the displaced Algerian revolution generation.

Soualem keeps it in the family in Tiberias, directing her lens towards her mother, Palestinian star Hiam Abbass of Succession, Ramy and Munich fame.

The film starts off as a character study of a Palestinian woman who rebelled against her conservative family to pursue her acting career. But Soualem gradually expands the scope of her subject to paint a deeply intimate portrait of a family torn apart by the Nakba - an event whose shadow still informs the makeup of the Abbass family.

Incorporating home videos and stock footage with a cinema verite approach in capturing the freewheeling rapport of Abbass with her sisters, the film takes an unexpected swerve in the last third to evolve into a meditation on grief and loss.

What finally transpires is a rich Palestinian family saga about hope and lost and found; about undying family bonds unchanged by distance and personal ideologies; about the cruelty of borders and the tattered state of the Arab world, and about the resilience of the Palestinian soul.

The film is not without blemishes. Soualem’s voiceover often feels intrusive and a statement of the obvious, while her position within the story is never fleshed out as it should be; the framing of Abbass in relation to her surroundings occasionally comes up short, such as when Soualem misses visual opportunities to explore her mother’s philosophical relationship to her home town.

It is a testament to Soualem’s vision and genuineness that none of these shortcomings manage to reduce the power of the film.

Soualem is not a cerebral filmmaker: the strength of her storytelling is rooted in an instinctive talent for drawing big emotions in the most unassuming of fashions. Bye Bye Tiberias is a prime example of her gifts: a thoughtful, piercing journey where Abbass valiantly bares her soul. And it’s easily the standout Palestinian film of the year.

Hesitation Wound is screening at the Zurich Film Fest in October. Behind the Mountains is at the BFI London Film Fest in October. Bye Bye Tiberias is at the London Film Fest and Chicago Film Fest in October.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.