From liberal West to Russia and China: How the Arab world lost the battle for democracy

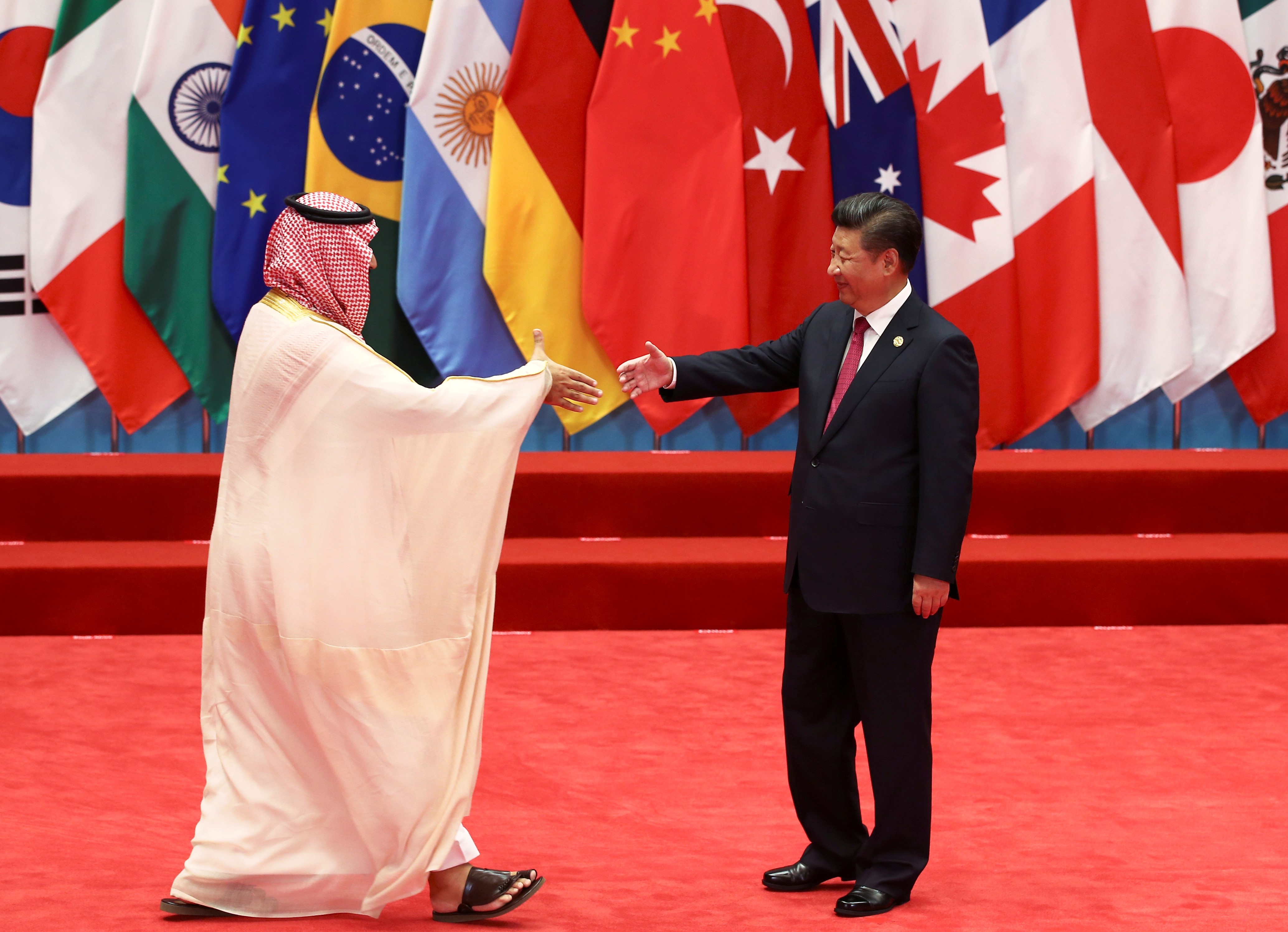

Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MBS) was reported to have recognised the right of China to deal with its Uighur population in the manner that it saw fit, all in the name of fighting Muslim extremism.

The crown prince’s failure to defend the rights of China’s Muslims might be easily explained by his need to find allies to burnish his international standing in the wake of global revulsion at his apparent involvement in the thuggish and brutal murder and dismemberment of the Saudi journalist, Jamal Khashoggi, in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

I believe, however, it signals a deeper and more profound reorientation of the Arab world away from the liberal West and toward the authoritarian powers of Russia and China.

A profound reorientation

Arab political thought over the last 150 years has focused primarily on reconciling its Islamic past with modernity. Political reform went hand in hand with religious reform, and although different types of religious reform were offered, they could easily be identified as corresponding to strands of democratic thought in the West.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

The counter-revolution is a repudiation in toto of dominant strains of Arab political and religious thought of the last 150 years

The importance of liberal thought, including for this purpose, Marx, on modern Islamic thought in the Arab world, not only generated a wide spectrum of religious reform projects - from advocating the privatisation of religion, to a neoliberal project of limited constitutional government combined with private ownership of property, to advocating radical redistribution of wealth – but it also produced a schizophrenic relationship with the liberal West.

On the one hand, reformist Arab Muslims admired the West’s accomplishments in liberal governance and scientific and material progress. On the other hand, they also resented the West for using their relative progress to further their imperialist ambitions that actively worked to undermine the capacity of Arab peoples to achieve effective self-government, reform and progress.

Going West

During the Cold War, however, widespread hostility to Soviet-style communism meant that even anti-imperialist Arab states, such as Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt, refused to join the Soviet bloc, and instead such states helped create the movement of the non-aligned states.

The same can be said about conservative Arab states. While suspicious of certain aspects of liberal modernity, they found more in common with the liberal West than the Soviet Union, and so they threw their lot in with the West.

They are promoting an authoritarian model of politics in which there are no citizens, only consumers

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, it seemed inevitable that the Arab world would gradually evolve toward constitutional government based on some kind of compromise between Islamists and liberals.

Indeed, this seems to have been the path followed in various Arab states in the post-Cold War era, with authoritarian regimes progressively ceding more space to civil society actors and allowing relatively freer elections in different domains of the state and civil society, albeit without permitting any effective challenges to the ruler.

From this perspective, the Arab Spring of 2011 can be viewed as the culmination of a century and half of political and religious thought that sought to achieve a system of limited constitutional government in the Arab world that could reconcile Islam and liberal modernity.

An authoritarian model

While some may wish to defend the counter-revolution on grounds of protecting the state from extremism, it is certainly obvious now that the parties leading it, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have no interest in establishing a democratic rule in the Arab world.

Rather, they are promoting an authoritarian model of politics in which there are no citizens, only consumers. Any attempt to assert political rights is met by charges of sedition. In this respect the attitude of Saudi Arabia and the UAE toward political dissent is the most accurate indicator of the future of politics in the Arab world.

Democracy is no longer taken for granted as the desirable goal of Arab politics, but is rather an existential threat to society

Egypt is in the process of formally amending its constitution to extend President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi’s rule to 2034 and to enshrine military supremacy over the state.

The counter-revolution, therefore, is not merely the repudiation of electoral democracy on the grounds that it empowered allegedly anti-democratic Islamists; rather, it is a repudiation in toto of dominant strains of Arab political and religious thought of the last 150 years.

Democracy is no longer taken for granted as the desirable goal of Arab politics, but is rather seen as an existential threat to society that must be confronted and contained at every turn. Any kind of popular politics is viewed as a threat to "national unity", and therefore must be aggressively suppressed.

Unlike pre-Arab Spring politics, when at least lip-service was given to political ideals such as democracy and human rights, the only value of the counter-revolution is state survival.

And in lieu of political rights, the state’s only obligation is to protect its hapless population from the threat of social collapse that would result from any form of democratisation.

In exchange for a complete surrender of political agency, the state suggests that it will try to improve their subjects' standards of living, but without making any provision to hold itself accountable for failing in this aspiration.

Such a dystopian conception of politics would have been impossible, either during the Cold War, or in the period of unipolar American dominance following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The rise of Russia and China

But in the new, multi-polar, transactional world of international relations promoted by the Trump administration, Arab autocracy sees in Russia and China durable models of authoritarian politics based in the shared value of contempt for pluralistic, competitive democracy as a threat to the integrity of the state.

The rise of China is especially attractive to Arab autocrats because it seems to vindicate their hope to achieve development without giving up any of their power, although they are more than happy to sacrifice development, if they believe that it would lead to demands for democratisation.

Mohammed bin Salman's willingness to endorse Chinese policy toward its Muslim minorities, from this perspective, is more than a tactical decision.

It represents the rise of a new alliance of global autocracies united in a shared belief that democracy is dangerous, and that states must be given absolute power to manage social and political change within their own borders without the inconvenience of accountability to their people, or the notion that individual rights can stand in the way of their plans.

It is not surprising, then, that the Saudi crown prince did not object to China’s treatment of its Muslim minorities: the new ideology of Arab autocracies rejects any kind of transnational solidarity, whether liberal or Islamic.

The indifference to the suffering of the Uighurs, therefore, and the Arab autocrats' support of Islamophobia in the West, is a harbinger of things to come.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.