'Anarchist Cookbook' acquittal turns spotlight on 'draconian' UK terror law

The acquittal of a London bus driver charged with terrorism offences for possessing a bomb-making manual available for purchase online has brought scrutiny on a far-reaching anti-terrorism provision used to prosecute people for holding documents despite no evidence they are planning an attack.

Cleared at the Old Bailey on Friday, Daniel Creagh, a 27-year-old convert to Islam, faced more than 10 years imprisonment after police searched his North London home in March and found a version of The Anarchist Cookbook on his phone, and £560 ($780) in counterfeit £10 notes.

Creagh was charged last year under Section 58 of the Terrorism Act for possessing a document “likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism”, though prosecutors stressed that he was not accused of planning an attack. He also faced one count of control of counterfeit currency.

On Friday, Creagh was found not guilty on both counts.

In a statement outside the court, he called for the UK's independent watchdog of counter-terrorism legislation to launch "an immediate and full inquiry" into his case and thanked his barrister David Gottlieb and solicitor Tasnime Akunjee.

"I have never supported violence or terrorism in any form. The police agreed I was not an extremist. The judge said he would not want to send me to prison if I was convicted," said Creagh.

"I am proud of my Muslim faith. This does not make me a criminal for browsing the internet."

It is the second time in months prosecutors have been unable to secure conviction based on Section 58, which some analysts say is one of the most controversial parts of Britain’s anti-terror arsenal. Others have argued that the provision is necessary to provide jurors with tangible proof of an ideology.

Creagh, who suffers from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, left school at 15 then served more than five years in prison on drug and robbery convictions before converting to Islam.

He claimed to have downloaded an edition of The Anarchist Cookbook “accidentally” while he was looking for information about the drug crystal meth.

He said that he had been watching the Netflix series Breaking Bad which fuelled an interest in the drug.

Creagh used to run a dawah (preaching Islam) stall in Leicester Square and told court he planned to throw the fake notes in the air to attract people to talk to him about the religion.

But police officer Matthew Hamilton, a computer forensics expert, said that Creagh must have taken "positive steps" to download the cookbook and it was "highly unlikely" he saved it by accident, jurors heard.

His web searches shortly before the download were contrary to his claim he "stumbled across the document whilst searching for how to make crystal meth", he added.

These included searches for "is the anarchy cookbook illegal", "forbidden knowledge" and "Hadiths on killing".

Hadiths are the reported teachings of the Prophet Muhammad which represent the second most important source of Islamic law after the Quran.

Yet the prosecution went to lengths to explain that the case was not about Creagh’s religious beliefs and that he was not charged with “having the cookbook in order to himself conduct a terrorist act.”

Creagh argued differently, claiming he was only prosecuted on the basis of his religion, and that he had investigated the legality of the book because he was afraid that as a Muslim his internet history “can be linked to terrorism".

“So much hysteria around Muslims,” he told jurors. “If I was a Catholic, I may not be here.”

If I was a Catholic, I may not be here

- Daniel Creagh

With versions of The Anarchist Cookbook available for purchase online at Amazon and Waterstones, Creagh said that he did not think that a book that authorities “associate with terrorism could possibly be sold by a multi-million online company".

'Draconian'

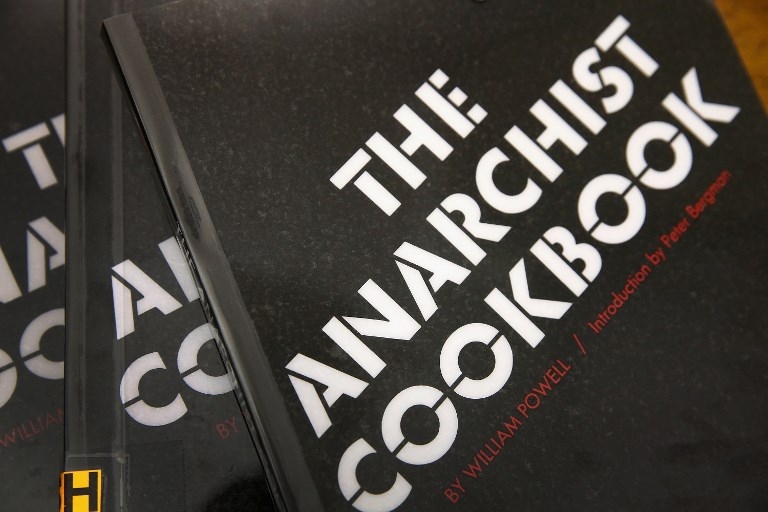

The Anarchist Cookbook was written in the US in the early 1970s and is associated with the American counterculture and protests against the Vietnam War.

"The book is essentially a handbook on how to engage in active resistance against what the author believes is a unjust government," Doug Weeks, a counter-terrorism expert, told Middle East Eye.

“There are numerous problem areas in the book such as how to build bombs, booby traps, anti-personnel devices, and debilitating chemical agents.”

British authorities have not banned the book outright, but have used terrorism laws to prosecute some for holding it, usually in cases where defendants have been involved in other suspicious activity.

In 2010, Ian Davison and his teenage son Nicky, members of a violent neo-Nazi group, were imprisoned under anti-terrorism law for manufacturing ricin and their possession of the book, and in 2011, Terence Brown was imprisoned for distributing the book as well as al-Qaeda training manuals.

In past cases, some people have acted on things based in these texts

- Raffaello Pantucci, Royal United Services Institute

But in October, Josh Walker, a student who spent six month fighting for the Kurdish-led YPG militia against the Islamic State (IS) group in Syria, walked free after having been charged for possessing the document.

Like Creagh, he had been prosecuted under Section 58 of the 2000 Terrorism Act, because as the law states, he possessed information “likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism”, though prosecutors acknowledged he was not plotting an attack.

Sweeping provision

Legal challenges have been brought against the provision on the basis that it gives authorities sweeping powers that can criminalise a whole host of information, opening the door for journalists working on national security issues to be prosecuted for holding sensitive information.

In 2008, the Court of Appeal clarified that Section 58 would only be applicable to “information that would typically be of use to terrorists, as opposed to ordinary members of the population”.

But Rizwaan Sabir, a criminologist specialising in the study of British counter-terrorism policy, still views section 58 as “draconian".

“It ignores the reason why a person holds or views such information or what they intend to use it for,” he said.

“The reasons why you might possess The Anarchist Cookbook or a military training manual is irrelevant. It is the nature of the information that is a crime; not the intention of the person who views or possesses it.”

In 2008, Sabir, then a student researching Islamic militancy at Nottingham University, was arrested under the Terrorism Act for downloading an al-Qaeda training manual from the US government's website before being cleared and receiving damages from authorities.

“Terrorism laws are only ever meant to be used against ‘terrorists,’ he added. “When the state acquires such draconian powers that disregard criminal intent, the temptation to use them becomes ever stronger.”

Britain no longer bans books but it does ban Muslims from owning certain books

- Arun Kundnani, expert on counter-terrorism policy

Describing The Anarchist Cookbook as "an ABC on how to make a bomb”, Raffaello Pantucci, director of International Security Studies at the Royal United Services Institute, argued that Section 58 can provide tangible evidence to help explain a suspect’s ideology in court.

“Trying to prosecute someone on the basis of ideology means that someone has to explain the ideology, then explain why it’s problematic to 12 jurors who have never encountered it before. The document is a way of binding a case to an ideology, something more concrete you can point to.

“If you have certain books or documents that radicals tend to have, in court you can point to those documents as being related to terrorism. In past cases some people have acted on things based in these texts.”

Arun Kundnani, a visiting professor of media, culture and communication at New York University and an expert on counter-terrorism policy, said that Creagh appeared to have been singled out because he is Muslim.

"Britain no longer bans books but it does ban Muslims from owning certain books. The meaning of these prosecutions is that they preemptively criminalise Muslims who are not terrorists.

“We should be deeply concerned that someone has appeared in court because of a book they own, and should be outraged at the hypocrisy of a government that calls freedom of speech a fundamental British value.”

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.