Nakba: Why the Zionists expelled Palestine's Arab population

In 1946, the population of Palestine numbered 1.2 million Arabs and around 600,000 Jews. There were more Arabs than Jews in 50 of Palestine's 60 districts.

The 1948 Arab-Israeli war would reverse the demographic ratio: around 800,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled from their homes, dispossessed of their property, and dispersed into refugee camps throughout the region.

After the publication of the Peel Commission report in 1937, world powers began invoking the partition of Palestine - a two-state solution that necessarily implied a transfer of populations. David Ben-Gurion, then chairman of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency, made no secret of his intentions: a Jewish state with too many Arabs was not a viable solution.

Today, the works of both Arab historians and Israeli "new historians" have definitively dismissed Zionist theories holding Palestinians accountable for the forced exile. And yet, a certain narrative aiming to absolve Israel of any responsibility whatsoever continues to be put forward.

Security reasons?

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

First, let's look at the so-called issue of security. According to the Zionist historical narrative, the expulsions did indeed take place, but only to ensure that no potential enemy was left behind as Jewish forces progressed.

The security argument doesn't hold water, however. For one thing, more than 70 massacres against Arab civilians and unarmed soldiers were perpetrated by Zionist units. Furthermore, had security truly been an issue at the time, the deportations would have stopped with the end of the war and the signing of the armistice agreements.

Obviously, that didn't happen. Arab towns and villages in Israel would continue to be emptied by Israeli forces throughout the 1950s.

Among these were the village of Abu Ghosh, whose 105 inhabitants were deported in 1950 to the Transjordan border, and the coastal village of al-Majdal, whose inhabitants were expelled to the Gaza Strip from 1949 to late 1950 to make way for a transit camp for Jewish immigrants. The port city of Ashkelon is at the site today.

Housing crisis

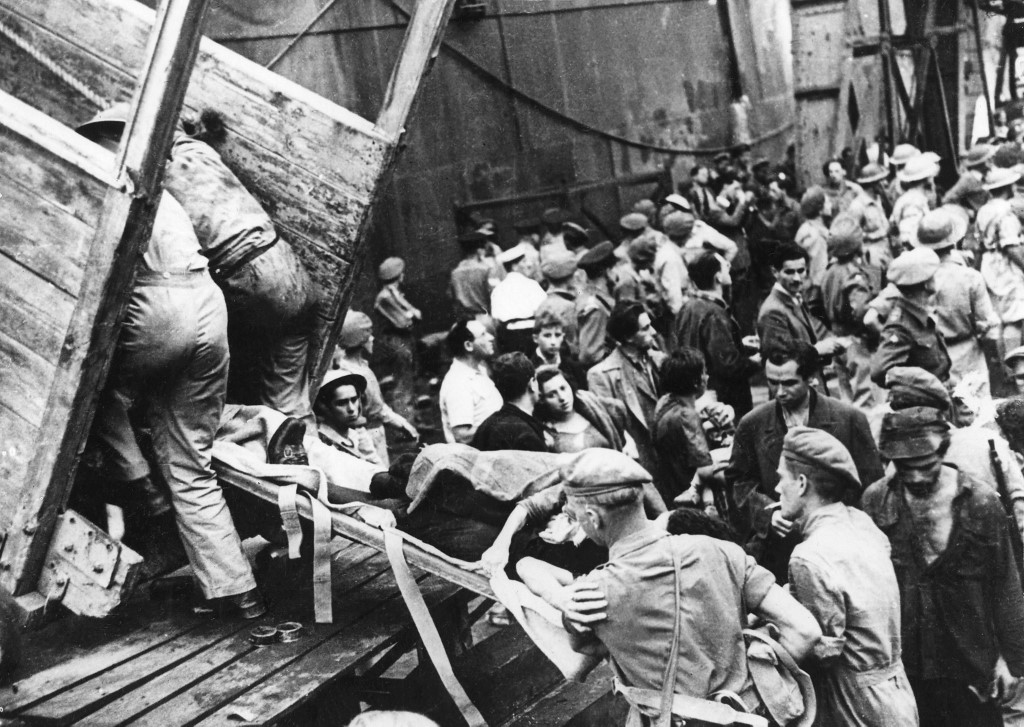

Along with population-transfer issues, Jewish Agency authorities were under increasing pressure to give shelter to the hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors and Jews from other Arab countries who were arriving in Palestine.

In addition, immigration remained steady between the proclamation of the state of Israel on 14 May 1948 and the end of December 1951, during which period the Jewish population of Israel approximately doubled to more than 1.3 million. While waiting to be given housing, newly arrived immigrants were crammed into squalid transit camps.

Custom had it that ownership was automatically granted to anyone who managed to move a bed into a private residence and spend the night in it

The Nakba helped to resolve the problem in part. During the 1948 exodus, thousands of Jews moved into vacated Arab dwellings: 45,000 found housing in the outskirts of Jaffa; 40,000 settled in central Haifa; 8,000 moved to Ramla and Lydda, renamed Lod; and 5,000 went to Acre. Jewish Agency officials supervised the operations and verified, insofar as possible, that the accommodation was brought up to standard.

Yet, the housing supply was still far from meeting demand. Though an estimated 140,000 to 160,000 immigrants could move into the former Arab dwellings, nearly 240,000 people had immigrated to Israel in 1949 alone.

Custom had it that ownership was automatically granted to anyone who managed to move a bed into a private residence and spend the night in it. In June of 1948, Jewish soldiers would enter Abbas Street in Haifa at 6am. Some were wounded. They drove out the Arab owners, emptied the homes, and moved in with their own belongings. The soldiers told authorities that they had fought for Israel but had never been granted housing.

Immigrant uprisings

Lengthy administrative procedures and oftentimes deplorable living conditions in cities, together with a lack of employment and of any prospects whatsoever, would lead to the early uprisings. In April 1949, 300 immigrants took to the streets of Tel Aviv and attempted to storm the Knesset, which was located at the time in an abandoned cinema.

In the weeks that followed, several hundred immigrants would ransack the premises of the Ministry of Integration, and dozens more, armed with sticks, would march from Jaffa to the Knesset, where they managed to break through the front gates.

The events tell of the strain that arriving populations were putting on Zionist authorities, while informing our understanding of the continued expulsions of Palestinians in Israel, even after the 1949 armistice agreements were signed between Israel and neighbouring Arab states.

Golda Meir, the labour minister from 1949 to 1956, played a pivotal role in the Israeli housing programme. Having arrived from Ukraine in 1921, Meir was a leading figure of left-wing Zionism who would hold key positions in the Jewish Agency and become a special adviser to Ben-Gurion.

As labour minister, she would implement major public housing projects. Within a few months, thousands of homes were built: two-storey buildings divided into two-room flats, small prefabricated houses, and even makeshift wooden huts. The fledgling Jewish nation had to defuse the newly arrived immigrants' anger by whatever means possible.

Though large-scale public works projects provided jobs and income to thousands of immigrants, countless others were left waiting in transit camps, and funds needed to be found to finance construction.

Spoils of war

Though the fledgling state of Israel was certainly helped by sizeable donations pouring in from abroad, it also relied heavily on the spoils of war: during the Nakba, thousands of Arab warehouses, shops, businesses and factories were seized.

In his book 1949: The First Israelis, historian Tom Segev reports that the Israeli army seized nearly 1,800 lorries loaded with goods in Lydda, whereas in Jaffa, in the weeks following the occupation of the city and the forced departure of its inhabitants, £30,000 ($37,000) worth of goods were looted on a daily basis by Jewish soldiers and civilians.

In Haifa, the government seized Arab safety-deposit boxes worth $1.8bn. Likewise, jobs once held by Arab populations were handed over to immigrants. In Ramla, some 600 shops abandoned by former Arab residents were distributed to newcomers and veterans.

However, in 1950, thousands of Jews were still unemployed, forcing the Israeli government to make what the Zionist movement considered a radical decision: to put a cap on immigration. Between 1951 and 1952, the number of new arrivals dropped from around 173,000 to 24,000, and in 1953 to around 10,000.

Shedding light on the 1948 Palestinian exodus reveals not so much the question of "how," but that of "why" - why the creation of Israel, a state with a Jewish majority in a predominantly Arab territory, consistently involved the expropriation and expulsion of Arab inhabitants. The first Arab-Israeli war was not the reason used by Zionist fighting units to achieve their goal; it was the means.

This piece was translated from the MEE French edition.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.