France’s Operation Barkhane and Saharan ghosts

On 1 August, France officially launched an “anti-terrorist” military campaign, code-named “Operation Barkhan”, across Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad - the Sahel countries known as the “Sahel G5”.

The operation involves the deployment of at least 3,000 troops, some 20 helicopters, 6 fighter planes, three drones and 200 armoured vehicles. It will also make use of basing facilities at Atar (Mauritania), Gao (Mali), Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), Niamey (Niger) and Ndjamena (Chad), as well as a number of “forward” or “control” bases such as Tessalit (Mali), Madama (Niger), Faya-Largeau and Zouar (Chad), and perhaps elsewhere.

Operation Barkhan is being portrayed as a fusion between Operation Serval, the codename of France’s military intervention in Mali in 2013, and the much older Operation Épervier, the codename of the ongoing French military presence in Chad, launched in 1986 to protect Chad from Libyan invasion.

What goes into the choice of such codenames? Military analogies are clearly important. The Serval is an African wild cat with the desirable military qualities of speed, agility, camouflage, acute acoustics, etc. Épervier, which means ‘Sparrowhawk’ in English, has the qualities of a fighter plane diving down and destroying its prey on the ground, as French fighter-bombers did in destroying Colonel Muammar Gaddaffi’s invading army. Barkhan is the name of a crescent-shaped sand dune. It is moved forward by the prevailing wind, with its two outstretched, crescent-shaped arms gathering in and smothering all before it.

Given Barkhan’s objective of ridding the region of terrorism, albeit mostly those “jihadists” who fled into Niger, Libya and Chad from Operation Serval, the codename is apposite. However, if the French high command had thought more about the etymology of the word, it might have gone for another animal name.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

The word barkhan is of Russian-Turkistan origin, said to have been coined by a Russian naturalist, Alexander von Middendorf, in 1881. The worrying aspect of it for France is not the Russian-Turkistan association, but the year 1881. While von Middendorf was busy coining the word barkhan for his dunes, France was experiencing a military nightmare in the middle of the Sahara.

The story of the disastrous Flatters expedition of 1880-81 is imprinted on the French colonial psyche, partly because of the absurdity of the project, partly because of its foolhardy planning and leadership, but mostly for its gruesome and grizzly details, which so shocked France that a halt was placed on further colonial penetration into the Sahara for almost 20 years.

Flatters set out from Ouargla in November 1880 at the head of a mixed column of over 90 men to reconnoitre a route for a railway across the Sahara. Such a grandiose scheme, designed to bring France closer to her Sahelian and West Africa territories, had been given impetus by the Americans succeeding in building a railway across their continent 11 years earlier.

The eve of their departure was celebrated with a grand dinner and the finest champagne, but also much nervousness, as local Chaamba tribesmen warned that they would run into trouble if they tried to enter Tuareg territory.

As the column headed south, Tuareg drew Flatters deeper into their country, before dividing his force at a water hole and massacring half of them. The column had got to within 200 kms of today’s border with Niger. The survivors were allowed to escape, but only for the Tuareg to play cat and mouse with them.

First, Tuareg offered them dates that had been crushed with efelehleh (Hyoscyamus muticus falezlez), one of the world’s most deadly plants. Most of those who ate it died in delirium and agony. The survivors then watched the Tuareg decapitate three of their Chaamba guides (most of whom, knowing the ways of the Tuareg, had refused the dates), while their accompanying Tidjaniya mokhadem (holy man) was split with a single blow of a broadsword from head to hips.

The remaining survivors continued their desperate trudge northwards, with those falling asleep being killed and eaten, as cannibalism became the means of survival. The last surviving Frenchman, the ailing Sergeant Pobéguin, was shot and eaten after much discussion as to whether a Frenchmen should not be treated with more respect. On 4 April 1881, 11 half-dead Chaamba crawled into Ouargla to tell the tale.

Those involved in Operation Barkhan will not wish to be reminded of the symbolism and memories of 1881.

However, the Flatters expedition was by no means either the most gruesome or the most shameful of France’s many military exploits in the Sahara-Sahel. Indeed, many members of the expedition exhibited great courage and bravery. Those epithets go to the Voulet-Chanoine mission of 1898-99, which is unsurpassed in the annals of French African colonial history for both its lunacy and atrocities, and which, unfortunately for Operation Barkhan, is a tad closer to both its own field of operations and local memories.

The expedition set out from Dakar in November 1898 to conquer the Chad basin and unify all those French territories along its way. Tragically for the peoples of the Sahel, the mission’s two commanders, Captain Paul Voulet and his adjutant Lt. Julien Chanoine, had “form”. A British historian described them as “psychopaths in uniform”. Indeed, Voulet had even told the governor of French Sudan that he would crush any resistance by burning villages.

Voulet’s fellow officer colleagues described him as “having a true love of blood and cruelty”; Chanoine as “cruel out of cold-bloodedness as well as for pleasure”. The expedition butchered its way across the Sahel in what was described as an orgy of pillaging, raping and killing. The number of Africans killed is not known, but estimated in the thousands.

The French military command may say that this is all “just history”. That is true, but history does not belong to yesterday. It plays a major part, through multiple perceptions, in determining peoples’ understanding of the present and therefore how they act towards it.

The Sahel’s political and military leaders, and no doubt many citizens as well, will welcome Operation Barkhan as their protection from terrorism. But France and the Sahel’s leaders would do well to take note of the sentiments of Niger’s highly respected civil society organisations that greeted President Hollande in Niamey on 18 July. They denounced the presence of French forces, calling it the “creeping colonisation” of the country through the establishment and maintenance of new military bases under “the false and overused pretext of the war against terrorism.”

“The real reason for France’s presence and its reoccupation of these countries,” they said, “is to monopolise the natural resources and to terrify the countries’ leaders to remain subject to France’s wishes.” We shall see.

- Jeremy Keenan is a Professorial Research Associate at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies. He has written many book including The Dark Sahara (2009) and The Dying Sahara (2012). He acts as consultant on the Sahara and the Sahel to numerous international organisations, including the United Nations, the European Commission and many others.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

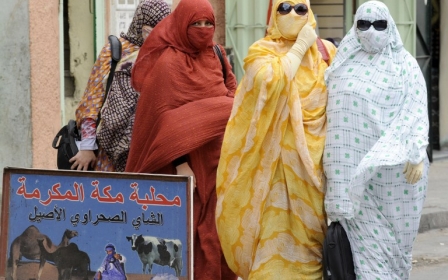

Photo credit: A Tuareg celebration in Sbiba. Most of the men are wielding the takouba, the Tuareg sword (Wikicommons)

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.